Isabelle Kenyon’s pamphlet, Growing Pains (published by Indigo Dreams in 2020), is an exploration of childhood, womanhood and personal value. What’s great about Kenyon’s poems is how they are full of contradictions, for instance in her poem When the worms came, she flits between the innocence and feral nature of children in one short poem. There are the ‘jackals, brandishing sticks’ alongside those who ‘offered their squatting form / a shield’. She also has the delightful ability to give us a dark turn, for instance in the same poem, which ends with ‘and enacted Lord of the Flies / with their worms as Piggy.’ While Kenyon also discusses what it means to be a woman and how society often views them in This is a man’s, man’s, man’s world: ‘measured for worth… from hip to hip to birth a child / hymen intact?’ While in Value, she talks about women’s worth being judged by ‘the number of boys in bed… the lack of ring on my finger… the space between my thighs’. She encapsulates so many of the feelings women experience on a daily basis, while also throwing in some humour. For instance, in The Periodic Table, she acknowledges how a woman’s body can invoke fear in men, especially in relation to periods. In this simple poem, Kenyon jokes about telling her brother about bleeding from the uterus and how ‘(he’ll thank me one day)’. Moreover, Kenyon also confronts some of the modern issues we have in the world. From being defined and tracked by our search history and background (‘Value: ‘Soon I am / my search history’), loneliness in an adult world (Spaces: ‘crying in a cubicle quietly’), the pressure to earn money (Sometimes I feel so alive with you I can’t breathe: ‘£ is a weary art’), and consent (Cryptic Consent: ‘No is a / sliding scale you negotiated’). Kenyon’s pamphlet is teeming with images, small moments described in detail, but also big concepts and issues, leaving the readers wanting more. She expresses herself with honesty and a mixture of delicacy and sharpness, which is not an easy task! I look forward to reading more of her work in the future. To read more and buy a copy of Growing Pains , visit: Fly on the Wall Press (for a signed copy!) Follow Isabelle on Twitter: @kenyon_isabelle

0 Comments

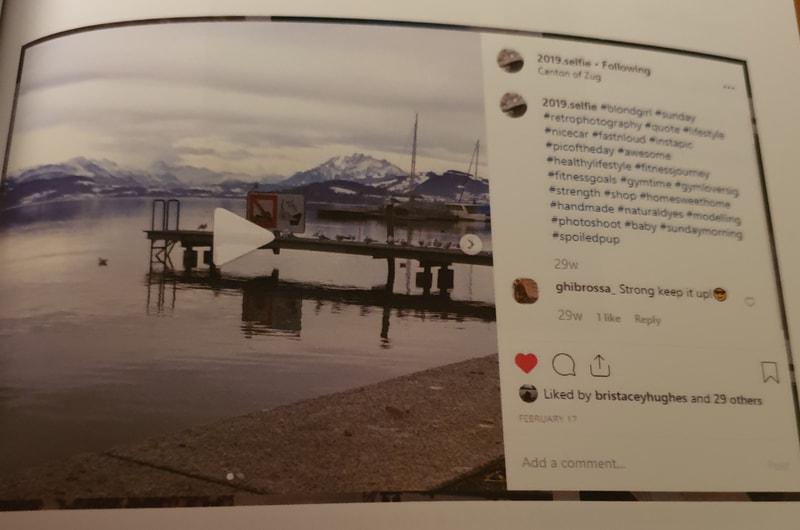

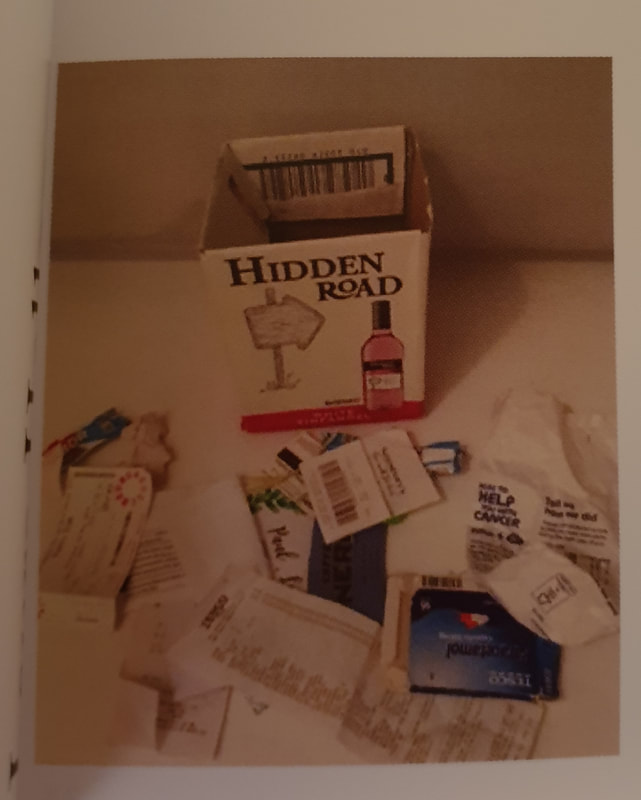

Recently, I was lucky enough to be sent a review copy of Matthew Haigh’s collection, Death Magazine, published by Salt (2019). From the outset, readers are confronted by a quote from J. G. Ballard, ‘How do we make sense of this ceaseless flow of advertising and publicity, news and entertainment, where presidential campaigns and moon voyages are presented in terms indistinguishable from the launch of a new candy bar or deodorant?’ From this springboard, Haigh’s poems encapsulate his own thoughts intertwined with words taken from various media, also mixed with reflection, absurdity and tenderness. Separated into sections, including ‘fitness’, ‘features’, ‘lifestyle’, ‘beauty’, ‘wellness’ and ‘advice’, it uses its structure to offer reflection on the magazine form to highlight the confusing messages readers often receive from the media and the world around them. As the Ballard quote expresses, with so many messages, all being merged regardless of importance, how do we begin to decipher anything real? The introductory poem 6 essential tips for transferring your consciousness to the cloud is the perfect way to begin the collection. Using a modern concept of the cloud, Haigh injects humour and absurdity into the concept by discussing it in terms of humans having no body. For instance, I really enjoyed parts such as, ‘a look at the products you won’t be using when you have no skin’ and ‘The Eternity Itch: preparing for a life without orgasm’. Moreover, I loved the hanging ending, ‘I Can’t Exist Like This: what to do when’, highlighting the lack of ideas about where exactly we are heading as humans in the face of such developments and progress. The other thing I loved about Haigh’s poems are the moments of tenderness, such as in We Will Not Become the Cloud, the Cloud Will Become Us, when he writes, ‘51%...... I’d be hanged in some places just for loving him’. Also, in How Adored Is the Pink Authority, when he writes, ‘I adore the sight of you in a dressing gown, but only via a mirror,’ which is both loving and self-conscious all at once. The interesting thread throughout is the links to technology and how it bleeds into every aspect of our lives. For instance, in Treating Depression with H. R. Giger, he says, ‘I only wonder: is beauty cold as data? Is beauty in data – am I supposed to see beauty in a camel spider?’ This is in reference to watching YouTube videos when feeling depressed, which is a commonplace experience and does really make the readers wonder what we are meant to take from watching odd videos online, as most of us do at some point or another! Another great poem is to his deceased aunt in relation to looking after the Sims characters she has left behind, in which he talks about a character whose chip fan goes on fire and she cries, writing ‘I can’t console her’. This is a great mirror of how he probably felt writing about the loss of his aunt, which is an interesting method of mourning someone, as well as the use of ‘console’, which links with grief and technology simultaneously. There is also a fascination with identity and maleness. The sometimes violent and harsh aspects of human identity are presented through the everyday, for example when he discusses a man having a nightmare in We Are like the Dreamer who Dreamer and Then Lives Inside the Dream, writing ‘as he runs he knows for certain that the only way to feel this brutally alive is if something huge really did attack.’ Furthermore, in Reptile Your Relationship, he says, ‘You may have been grotesque for some time’, as though an uncomfortable truth has slowly been realised. Though, the clever aspect of this is after a whole poem of suspicion and uncertainty, Haigh finishes with, ‘If any of these scenarios applies to you, shrug.’ Thus, presenting an interesting turn. With regard to maleness, this is present throughout. Though there is a section entitled ‘advice’, which takes on a Q&A style, offering comments such as, ‘Modern day totems perpetuate unrealistic goals by shaming men into inadequacy’ and ‘We consistently encourage men to get a grip’, and lastly, ‘I am a downloaded copy of my entire life’. Maleness is not a concrete concept here and it’s interesting to see reflections on a new definition of what being a man could be. This collection offers an exploration of the consciousness, absurdity, oddness and complexities experienced as a modern man, and, a modern human. Some of the images and juxtapositions had me laughing, while others were so perceptive, they triggered knowingness or sadness. I hugely recommend it and thanks to Matthew for the read! To read more and buy, visit: https://www.saltpublishing.com/products/death-magazine-9781784632069 Follow Matt on Twitter: @MattHaighPoetry  It’s great to see a group of female poets, experimental female poets no less, producing an anthology with such exciting content. When I heard about the Crested Tit Collective, I immediately wanted a review copy. Luckily, when I had it in my hands, it did not disappoint. First off though, let me explain who the CTC are. An explanation is provided inside the cover as follows: The anthology includes work from: Tiffany Charrington, Cat Chong, Laura Hellon, Briony Hughes, E.P. Jenkins, Martina Krajňáková and Sophie Shephard. The anthology dives straight in with some visual work from Tiffany Charrington. The page is full of coloured lines of text. The beginning is an intriguing declaration of, ‘She wept when she heard I was another girl’, which is a heart-breaking and curious start to this anthology. After that, it’s an assault on the senses, interspersed with fragmented emotions and images, such as, ‘she wept dragged in rooms folding notes traces between tongues.’ The weeping mixed with the dragging and the intimacy of the notes and tongues makes for an interesting combination. What follows are different offerings from the female poets, ranging from 'found' words on a variety of objects on different days by Laura Hellon. This led to some great and jarring combinations, for instance, ‘Debit my partners’ and IKEA family records’ and lastly, ‘Add CONTACTLESS onion’. Other pieces include poems by Briony Hughes inspired by social media posts, including screenshots and the accompanying hashtags. It offers some feedback and reflection on the daily obsession to be noticed online and make your mark in this digital age in a world of contradiction. Some particular lines in this vein are, ‘the internet never forgets’ and ‘i’ll sit in starbucks and read poetry about the migrant crisis’and finally, ‘instagram poetry in gateway poetry’. Other poems are presented in a more straightforward way but often the content is odd/disjointed. There are some fantastic images also. I particularly enjoyed E.P. Jenkin’s poem When He Reads, in which there’s the line, ‘Too many, / Circuits, not enough lemons.’ The oddness of this juxtaposition is something that leads to lots of questions, which is one of the things I enjoy most about poetry. Also, Sophie Shepherd’s poem (Not) Having a coke with you (After Frank O’Hara), which is a deliciously humourous and playful tribute poem with a refrain adapted throughout. I particularly enjoyed parts such as, ‘And i guess me messaging you to tell you my friend saw you buying a coke at ten am / is not the same as having a coke with you’ and ‘then we can rot away our teeth together at the perfect cold to room temperature / I’d do that for you.’ There are also some combined cut up prescription text or information leaflets interspersed with poetry by Cat Chong. These were visually engaging and the added poetry gave these pieces a focus, especially lines such as, ‘your experience of living / is sufficient’ and, ‘Sometimes we believe /what’s important to us.’ The experience of pain is a universal feeling and some of the poems encapsulate this well. What struck me most was the hunger and initiative to experiment and innovate. Not every single poem was a masterpiece but every poem displayed originality, creativity and thought, which led me to believe that these writers show a lot of promise and I think there will be some exciting things to come from them. I haven’t focused on every single writer here but I, for one, will be keeping an eye on what all of them produce next.

Check out more about them: www.crestedtitcollective.com @CTCpoetry  Having published Anna twice in streetcake, I was keen to see more of Anna's writing. I was also curious as to whether the content of her chapbook would be similar to what I have published in streetcake. Turns out, it wasn't. Thankfully though , it didn't disappoint. For Taropoetics, Anna explains at the beginning of her chapbook that the writing process involved consulting five tarot cards shuffled and dealt at random once a week for an entire year. The free-written text was then collated and edited for the chapbook. Inspired by the works of John Cage, Jackson MacLow and Hannah Weiner (if you haven't checked out the mind-bending Clairvoyant Journal, you should!), the influence was quite clear. The poems; short combinations of words seperated by forward slashes, are very dense. I had to take my time reading them - only devouring a few at a time, before taking a break. However, it doesn't mean I wasn't enjoying them. Quite the opposite, I loved the way they appeared so concrete (like the poetry of Steve McCaffery), yet they were mixed with a certain tenderness. The unusual imagery also reminded me of Maggie O'Sullivan - I'm not going to wax lyrical about these writers- if you want to check them out, then that's great. So back to the imagery... The images were contradictory, violent, delicate. Some of my favourite sections include: (13): 'sharp capitals/cut/bring blood through/eye shadow/cheeks sucked in from the top/gaunt fear/list those purple days/soft lashes on bloody barbs/kohl shadow wipe/violet cringe/bloodshot curve...' (42): 'all my blood for yours/there is nothing left/to give/forgive it all/dim cling to wet coverage/wet walls/thin ground/fire burns surface grass on horizon/dry winds pull above/rakes trails into sand/volcanic space under...' Sometimes, there is also repetition used in Taropoetics. This in particular adds to the softer moments throughout the chapbook. At first, the format of the poems might seem daunting and you might be tempted to try to fully understand the process behind the poems but please don't - just enjoy the poetry for what it is. Just digest the brilliant images interwoven with language that can be both viscious and tender in the same breath. You can buy Anna's chapbook, Taropoetics, for £5 from The Knives, Forks and Spoons Press.  In three words, I would sum up this novel as succinct, creative and suffocating. I know what you're thinking; 'suffocating' is not a particularly positive word. However, I mean it in that you can't stop reading because as you do, the description keeps hitting you over and over, hardly giving you time to breathe. Equally, the presence of sand in the novel, all around the characters, in their food and drink, on their bodies, creates a sense of suffocation at all points. Yet, although the premise of an insect collector being imprisoned in a sand pit seems in some senses depressing and perhaps boring, Abe really makes sure that it is neither. So to the beginning but without ruining too much of the novel: we meet Niki Jumpei, an insect collector who has impulsively decided to visit some sand dunes somewhere in Japan to find insects, specifically sand beetles. By nightfall, desperately needing a place to stay, he ends up deep in a sand pit, seemingly offered hospitality by a woman who lives in a deteriorating house at the bottom. By morning, the ladder to freedom has been taken away and so begins Niki's fascination and hate for his imprisonment. What was interesting was that the protagonist, Niki, came to the dunes because he had a fascination with sand initially. He talks about how it 'flows' around the world and its 1/8 of a millimetre size. And in the novel, the sand does flow through it and it does seem to get into the smallest places. As you read, you can almost feel the sand on your skin, grating at you as it does Niki. His initial fascination soon becomes questioned by the woman he lives with in the dunes, who has lived with sand in a completely different way to him- it doesn't flow for her, it weights heavy on her body, her home, everything she owns. Sand for the woman destroys her possessions, soils food, killed her husband and child. Niki is educated about sand and a new way of life. Yet he schemes constantly, trying to find his escape. Yet almost like a case of Stockholm syndrome, Niki eventually finds comfort in the woman. If anything, he seems to be more attached to her than she is to him as Niki constantly notes her lack of sincerity. It almost seems she is merely desperate to have a man in the pit with her to help her clear the sand. Some may have found the minute detail in this novel a bit too liberally spread but I found them exciting to read. I became submerged in the claustrophobic sandy landscape and Niki's turmoil. Most interesting was that the exact thing that Niki wanted throughout the novel becomes meaningless. Although some may call this obvious, I still enjoyed this. When the ladder is finally returned and left unattended, what does Niki do? It leaves the readers with a few questions: what happens when you finally obtain the unobtainable? Moreover, what happens when you see the world from another perspective and it changes your priorities? A fantastic read for fans of succinct and alternative fiction. If you like unusual descriptions and facing a situation completely different to your own, this may just be the read for you...  Eileen R. Tabios’ THE OPPOSITE OF CLAUSTROPHOBIA is reminiscent of Ginsberg's “Howl” with the constant refrain of “I forgot” instead. This collection encompasses a huge range of content, from intimate reflections to broader observations about different cultures, places, religions and people. When I was reading, I simultaneously felt as though I was lying beside Tabios like a lover or confidant, as well as moving through the generations of her family or the past of her country. There is a continual pulling closer to and then transportation to miles away from a foreign land with a potentially dark history. There are also very poignant moments, such as “I forgot my mistake,” though Tabios then goes on to suggest quite the opposite. There is a lot of to and froing in this sense—tracing the past, reliving mistakes, reconsidering good and bad times, thinking about her history and what it means about who she is now. For this reason, I was sometimes unsure if Tabios is referring to herself or taking on numerous personalities in her poetry. Either way, the images pile on top of one another, like a constant deluge of water battering the reader. For instance, she wrote, “I forgot how quickly civilization can disappear, as swiftly as the shoreline from an oil spill birthed from a twist of the wrist by a drunk vomiting over the helm.” This image begins with a broad concept and slowly shrinks inwards like a hedgehog curling itself up to hide away from the world and protect itself, while the oil spill and the drunk vomiting over the helm imagery also reminds us of how careless we are as humans and how we are probably privy to our own destruction. It is hauntingly accurate and savage. Moreover, there are a lot of instances where the power of nature crept in: “I forgot the grandfather who willingly faced a fire, fist trembling at the indifferent sky” and “I forgot I saw a city bleeding beyond the window.” All of these images seem to be a reminder that there is a lack of control over nature, and much like Tabios’ poetry, they can suddenly wash over you, lick you like a fire and make you feel exposed like a landscape after being ravaged by a natural disaster. At other times, the writing is unsettlingly intimate, for instance, “I forgot you living somewhere along my spine. I forgot integral yoga to squeeze you more efficiently out of bone marrow.” I particularly love some other specific lines, for example, “I forgot the horizon is far, is near, is what you wish but always in front of you” and “I forgot you falling asleep in my skin to dream.” These lines are usually sweet but also tinged with an element of horror, hope, love, and the feeling that things can change right before your eyes. I really enjoyed this collection and I look forward to reading more of Tabios' work. You can purchase the collection from KFS |

Short reviews of books I've enjoyed and author interviews Archives

January 2022

Categories |

Member of the Society of Authors

Copyright © 2019 · All Rights Reserved · Nikki Dudley

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed